A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity.[1] The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy.[2]

A star’s life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star’s interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star’s lifetime, fusion ceases and its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole.

Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star’s apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time.

Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy.

Etymology

The word “star” ultimately derives from the Proto-Indo-European root “h₂stḗr” also meaning star, but further analyzable as h₂eh₁s- (“to burn”, also the source of the word “ash”) + -tēr (agentive suffix). Compare Latin stella, Greek aster, German Stern. Some scholars[who?] believe the word is a borrowing from Akkadian “istar” (Venus). “Star” is cognate (shares the same root) with the following words: asterisk, asteroid, astral, constellation, Esther.[3]

Observation history

See also: Stars in astrology

Historically, stars have been important to civilizations throughout the world. They have been part of religious practices, divination rituals, mythology, used for celestial navigation and orientation, to mark the passage of seasons, and to define calendars.

Early astronomers recognized a difference between “fixed stars“, whose position on the celestial sphere does not change, and “wandering stars” (planets), which move noticeably relative to the fixed stars over days or weeks.[6] Many ancient astronomers believed that the stars were permanently affixed to a heavenly sphere and that they were immutable. By convention, astronomers grouped prominent stars into asterisms and constellations and used them to track the motions of the planets and the inferred position of the Sun.[4] The motion of the Sun against the background stars (and the horizon) was used to create calendars, which could be used to regulate agricultural practices.[7] The Gregorian calendar, currently used nearly everywhere in the world, is a solar calendar based on the angle of the Earth’s rotational axis relative to its local star, the Sun.

The oldest accurately dated star chart was the result of ancient Egyptian astronomy in 1534 BC.[8] The earliest known star catalogues were compiled by the ancient Babylonian astronomers of Mesopotamia in the late 2nd millennium BC, during the Kassite Period (c. 1531 BC – c. 1155 BC).[9]

The first star catalogue in Greek astronomy was created by Aristillus in approximately 300 BC, with the help of Timocharis.[10] The star catalog of Hipparchus (2nd century BC) included 1,020 stars, and was used to assemble Ptolemy‘s star catalogue.[11] Hipparchus is known for the discovery of the first recorded nova (new star).[12] Many of the constellations and star names in use today derive from Greek astronomy.

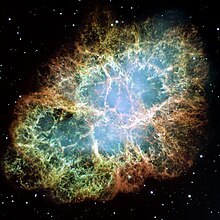

Despite the apparent immutability of the heavens, Chinese astronomers were aware that new stars could appear.[13] In 185 AD, they were the first to observe and write about a supernova, now known as SN 185.[14] The brightest stellar event in recorded history was the SN 1006 supernova, which was observed in 1006 and written about by the Egyptian astronomer Ali ibn Ridwan and several Chinese astronomers.[15] The SN 1054 supernova, which gave birth to the Crab Nebula, was also observed by Chinese and Islamic astronomers.[16][17][18]

Medieval Islamic astronomers gave Arabic names to many stars that are still used today and they invented numerous astronomical instruments that could compute the positions of the stars. They built the first large observatory research institutes, mainly to produce Zij star catalogues.[19] Among these, the Book of Fixed Stars (964) was written by the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, who observed a number of stars, star clusters (including the Omicron Velorum and Brocchi’s Clusters) and galaxies (including the Andromeda Galaxy).[20] According to A. Zahoor, in the 11th century, the Persian polymath scholar Abu Rayhan Biruni described the Milky Way galaxy as a multitude of fragments having the properties of nebulous stars, and gave the latitudes of various stars during a lunar eclipse in 1019.[21]

According to Josep Puig, the Andalusian astronomer Ibn Bajjah proposed that the Milky Way was made up of many stars that almost touched one another and appeared to be a continuous image due to the effect of refraction from sublunary material, citing his observation of the conjunction of Jupiter and Mars on 500 AH (1106/1107 AD) as evidence.[22] Early European astronomers such as Tycho Brahe identified new stars in the night sky (later termed novae), suggesting that the heavens were not immutable. In 1584, Giordano Bruno suggested that the stars were like the Sun, and may have other planets, possibly even Earth-like, in orbit around them,[23] an idea that had been suggested earlier by the ancient Greek philosophers, Democritus and Epicurus,[24] and by medieval Islamic cosmologists[25] such as Fakhr al-Din al-Razi.[26] By the following century, the idea of the stars being the same as the Sun was reaching a consensus among astronomers. To explain why these stars exerted no net gravitational pull on the Solar System, Isaac Newton suggested that the stars were equally distributed in every direction, an idea prompted by the theologian Richard Bentley.[27]

The Italian astronomer Geminiano Montanari recorded observing variations in luminosity of the star Algol in 1667. Edmond Halley published the first measurements of the proper motion of a pair of nearby “fixed” stars, demonstrating that they had changed positions since the time of the ancient Greek astronomers Ptolemy and Hipparchus.[23]

William Herschel was the first astronomer to attempt to determine the distribution of stars in the sky. During the 1780s, he established a series of gauges in 600 directions and counted the stars observed along each line of sight. From this, he deduced that the number of stars steadily increased toward one side of the sky, in the direction of the Milky Way core. His son John Herschel repeated this study in the southern hemisphere and found a corresponding increase in the same direction.[28] In addition to his other accomplishments, William Herschel is noted for his discovery that some stars do not merely lie along the same line of sight, but are physical companions that form binary star systems.[29]

The science of stellar spectroscopy was pioneered by Joseph von Fraunhofer and Angelo Secchi. By comparing the spectra of stars such as Sirius to the Sun, they found differences in the strength and number of their absorption lines—the dark lines in stellar spectra caused by the atmosphere’s absorption of specific frequencies. In 1865, Secchi began classifying stars into spectral types.[30] The modern version of the stellar classification scheme was developed by Annie J. Cannon during the early 1900s.[31]

The first direct measurement of the distance to a star (61 Cygni at 11.4 light-years) was made in 1838 by Friedrich Bessel using the parallax technique. Parallax measurements demonstrated the vast separation of the stars in the heavens.[23] Observation of double stars gained increasing importance during the 19th century. In 1834, Friedrich Bessel observed changes in the proper motion of the star Sirius and inferred a hidden companion. Edward Pickering discovered the first spectroscopic binary in 1899 when he observed the periodic splitting of the spectral lines of the star Mizar in a 104-day period. Detailed observations of many binary star systems were collected by astronomers such as Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve and S. W. Burnham, allowing the masses of stars to be determined from computation of orbital elements. The first solution to the problem of deriving an orbit of binary stars from telescope observations was made by Felix Savary in 1827.[32]

The twentieth century saw increasingly rapid advances in the scientific study of stars. The photograph became a valuable astronomical tool. Karl Schwarzschild discovered that the color of a star and, hence, its temperature, could be determined by comparing the visual magnitude against the photographic magnitude. The development of the photoelectric photometer allowed precise measurements of magnitude at multiple wavelength intervals. In 1921 Albert A. Michelson made the first measurements of a stellar diameter using an interferometer on the Hooker telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory.[33]

Important theoretical work on the physical structure of stars occurred during the first decades of the twentieth century. In 1913, the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram was developed, propelling the astrophysical study of stars. Successful models were developed to explain the interiors of stars and stellar evolution. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin first proposed that stars were made primarily of hydrogen and helium in her 1925 PhD thesis.[34] The spectra of stars were further understood through advances in quantum physics. This allowed the chemical composition of the stellar atmosphere to be determined.[35]

With the exception of rare events such as supernovae and supernova impostors, individual stars have primarily been observed in the Local Group,[36] and especially in the visible part of the Milky Way (as demonstrated by the detailed star catalogues available for the Milky Way galaxy) and its satellites.[37] Individual stars such as Cepheid variables have been observed in the M87[38] and M100 galaxies of the Virgo Cluster,[39] as well as luminous stars in some other relatively nearby galaxies.[40] With the aid of gravitational lensing, a single star (named Icarus) has been observed at 9 billion light-years away.[41][42]

Designations

Main articles: Stellar designation, Astronomical naming conventions, and Star catalogue

The concept of a constellation was known to exist during the Babylonian period. Ancient sky watchers imagined that prominent arrangements of stars formed patterns, and they associated these with particular aspects of nature or their myths. Twelve of these formations lay along the band of the ecliptic and these became the basis of astrology.[43] Many of the more prominent individual stars were given names, particularly with Arabic or Latin designations.

As well as certain constellations and the Sun itself, individual stars have their own myths.[44] To the Ancient Greeks, some “stars”, known as planets (Greek πλανήτης (planētēs), meaning “wanderer”), represented various important deities, from which the names of the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn were taken.[44] (Uranus and Neptune were Greek and Roman gods, but neither planet was known in Antiquity because of their low brightness. Their names were assigned by later astronomers.)

Circa 1600, the names of the constellations were used to name the stars in the corresponding regions of the sky. The German astronomer Johann Bayer created a series of star maps and applied Greek letters as designations to the stars in each constellation. Later a numbering system based on the star’s right ascension was invented and added to John Flamsteed‘s star catalogue in his book “Historia coelestis Britannica” (the 1712 edition), whereby this numbering system came to be called Flamsteed designation or Flamsteed numbering.[45][46]

The internationally recognized authority for naming celestial bodies is the International Astronomical Union (IAU).[47] The International Astronomical Union maintains the Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[48] which catalogs and standardizes proper names for stars.[49] A number of private companies sell names of stars which are not recognized by the IAU, professional astronomers, or the amateur astronomy community.[50] The British Library calls this an unregulated commercial enterprise,[51][52] and the New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection issued a violation against one such star-naming company for engaging in a deceptive trade practice.[53][54]

Units of measurement

Although stellar parameters can be expressed in SI units or Gaussian units, it is often most convenient to express mass, luminosity, and radii in solar units, based on the characteristics of the Sun. In 2015, the IAU defined a set of nominal solar values (defined as SI constants, without uncertainties) which can be used for quoting stellar parameters:

| nominal solar luminosity | L☉ = 3.828×1026 W[55] |

| nominal solar radius | R☉ = 6.957×108 m[55] |

The solar mass M☉ was not explicitly defined by the IAU due to the large relative uncertainty (10−4) of the Newtonian constant of gravitation G. Since the product of the Newtonian constant of gravitation and solar mass together (GM☉) has been determined to much greater precision, the IAU defined the nominal solar mass parameter to be:

| nominal solar mass parameter: | GM☉ = 1.3271244×1020 m3/s2[55] |

The nominal solar mass parameter can be combined with the most recent (2014) CODATA estimate of the Newtonian constant of gravitation G to derive the solar mass to be approximately 1.9885×1030 kg. Although the exact values for the luminosity, radius, mass parameter, and mass may vary slightly in the future due to observational uncertainties, the 2015 IAU nominal constants will remain the same SI values as they remain useful measures for quoting stellar parameters.

Large lengths, such as the radius of a giant star or the semi-major axis of a binary star system, are often expressed in terms of the astronomical unit—approximately equal to the mean distance between the Earth and the Sun (150 million km or approximately 93 million miles). In 2012, the IAU defined the astronomical constant to be an exact length in meters: 149,597,870,700 m.[55]

Formation and evolution

Main article: Stellar evolution

Stellar evolution of low-mass (left cycle) and high-mass (right cycle) stars, with examples in italics

Size comparison (radius and mass) of a red dwarf, the Sun, a supermassive blue supergiant, and a red giant.

Stars condense from regions of space of higher matter density, yet those regions are less dense than within a vacuum chamber. These regions—known as molecular clouds—consist mostly of hydrogen, with about 23 to 28 percent helium and a few percent heavier elements. One example of such a star-forming region is the Orion Nebula.[56] Most stars form in groups of dozens to hundreds of thousands of stars.[57] Massive stars in these groups may powerfully illuminate those clouds, ionizing the hydrogen, and creating H II regions. Such feedback effects, from star formation, may ultimately disrupt the cloud and prevent further star formation.[58] All stars spend the majority of their existence as main sequence stars, fueled primarily by the nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium within their cores. However, stars of different masses have markedly different properties at various stages of their development. The ultimate fate of more massive stars differs from that of less massive stars, as do their luminosities and the impact they have on their environment. Accordingly, astronomers often group stars by their mass:[59]

- Very low mass stars, with masses below 0.5 M☉, are fully convective and distribute helium evenly throughout the whole star while on the main sequence. Therefore, they never undergo shell burning and never become red giants. After exhausting their hydrogen they become helium white dwarfs and slowly cool.[60] As the lifetime of 0.5 M☉ stars is longer than the age of the universe, no such star has yet reached the white dwarf stage.

- Low mass stars (including the Sun), with a mass between 0.5 M☉ and ~2.25 M☉ depending on composition, do become red giants as their core hydrogen is depleted and they begin to burn helium in core in a helium flash; they develop a degenerate carbon-oxygen core later on the asymptotic giant branch; they finally blow off their outer shell as a planetary nebula and leave behind their core in the form of a white dwarf.[61][62]

- Intermediate-mass stars, between ~2.25 M☉ and ~8 M☉, pass through evolutionary stages similar to low mass stars, but after a relatively short period on the red-giant branch they ignite helium without a flash and spend an extended period in the red clump before forming a degenerate carbon-oxygen core.[61][62]

- Massive stars generally have a minimum mass of ~8 M☉.[63] After exhausting the hydrogen at the core these stars become supergiants and go on to fuse elements heavier than helium. Many end their lives when their cores collapse and they explode as supernovae.[61][64]

Star formation

Main article: Star formation

Artist’s conception of the birth of a star within a dense molecular cloud

A cluster of approximately 500 young stars lies within the nearby W40 stellar nursery.

The formation of a star begins with gravitational instability within a molecular cloud, caused by regions of higher density—often triggered by compression of clouds by radiation from massive stars, expanding bubbles in the interstellar medium, the collision of different molecular clouds, or the collision of galaxies (as in a starburst galaxy).[65][66] When a region reaches a sufficient density of matter to satisfy the criteria for Jeans instability, it begins to collapse under its own gravitational force.[67]

As the cloud collapses, individual conglomerations of dense dust and gas form “Bok globules“. As a globule collapses and the density increases, the gravitational energy converts into heat and the temperature rises. When the protostellar cloud has approximately reached the stable condition of hydrostatic equilibrium, a protostar forms at the core.[68] These pre-main-sequence stars are often surrounded by a protoplanetary disk and powered mainly by the conversion of gravitational energy. The period of gravitational contraction lasts about 10 million years for a star like the sun, up to 100 million years for a red dwarf.[69]

Early stars of less than 2 M☉ are called T Tauri stars, while those with greater mass are Herbig Ae/Be stars. These newly formed stars emit jets of gas along their axis of rotation, which may reduce the angular momentum of the collapsing star and result in small patches of nebulosity known as Herbig–Haro objects.[70][71] These jets, in combination with radiation from nearby massive stars, may help to drive away the surrounding cloud from which the star was formed.[72]

Early in their development, T Tauri stars follow the Hayashi track—they contract and decrease in luminosity while remaining at roughly the same temperature. Less massive T Tauri stars follow this track to the main sequence, while more massive stars turn onto the Henyey track.[73]

Most stars are observed to be members of binary star systems, and the properties of those binaries are the result of the conditions in which they formed.[74] A gas cloud must lose its angular momentum in order to collapse and form a star. The fragmentation of the cloud into multiple stars distributes some of that angular momentum. The primordial binaries transfer some angular momentum by gravitational interactions during close encounters with other stars in young stellar clusters. These interactions tend to split apart more widely separated (soft) binaries while causing hard binaries to become more tightly bound. This produces the separation of binaries into their two observed populations distributions.[75]

Main sequence

Main article: Main sequence

Stars spend about 90% of their lifetimes fusing hydrogen into helium in high-temperature-and-pressure reactions in their cores. Such stars are said to be on the main sequence and are called dwarf stars. Starting at zero-age main sequence, the proportion of helium in a star’s core will steadily increase, the rate of nuclear fusion at the core will slowly increase, as will the star’s temperature and luminosity.[76] The Sun, for example, is estimated to have increased in luminosity by about 40% since it reached the main sequence 4.6 billion (4.6×109) years ago.[77]

Every star generates a stellar wind of particles that causes a continual outflow of gas into space. For most stars, the mass lost is negligible. The Sun loses 10−14 M☉ every year,[78] or about 0.01% of its total mass over its entire lifespan. However, very massive stars can lose 10−7 to 10−5 M☉ each year, significantly affecting their evolution.[79] Stars that begin with more than 50 M☉ can lose over half their total mass while on the main sequence.[80]

The time a star spends on the main sequence depends primarily on the amount of fuel it has and the rate at which it fuses it. The Sun is expected to live 10 billion (1010) years. Massive stars consume their fuel very rapidly and are short-lived. Low mass stars consume their fuel very slowly. Stars less massive than 0.25 M☉, called red dwarfs, are able to fuse nearly all of their mass while stars of about 1 M☉ can only fuse about 10% of their mass. The combination of their slow fuel-consumption and relatively large usable fuel supply allows low mass stars to last about one trillion (10×1012) years; the most extreme of 0.08 M☉ will last for about 12 trillion years. Red dwarfs become hotter and more luminous as they accumulate helium. When they eventually run out of hydrogen, they contract into a white dwarf and decline in temperature.[60] Since the lifespan of such stars is greater than the current age of the universe (13.8 billion years), no stars under about 0.85 M☉[81] are expected to have moved off the main sequence.

Besides mass, the elements heavier than helium can play a significant role in the evolution of stars. Astronomers label all elements heavier than helium “metals”, and call the chemical concentration of these elements in a star, its metallicity. A star’s metallicity can influence the time the star takes to burn its fuel, and controls the formation of its magnetic fields,[82] which affects the strength of its stellar wind.[83] Older, population II stars have substantially less metallicity than the younger, population I stars due to the composition of the molecular clouds from which they formed. Over time, such clouds become increasingly enriched in heavier elements as older stars die and shed portions of their atmospheres.[84]

Post–main sequence

Main articles: Subgiant, Red giant, Horizontal branch, Red clump, and Asymptotic giant branch

As stars of at least 0.4 M☉[85] exhaust the supply of hydrogen at their core, they start to fuse hydrogen in a shell surrounding the helium core. The outer layers of the star expand and cool greatly as they transition into a red giant. In some cases, they will fuse heavier elements at the core or in shells around the core. As the stars expand, they throw part of their mass, enriched with those heavier elements, into the interstellar environment, to be recycled later as new stars.[86] In about 5 billion years, when the Sun enters the helium burning phase, it will expand to a maximum radius of roughly 1 astronomical unit (150 million kilometres), 250 times its present size, and lose 30% of its current mass.[77][87]

As the hydrogen-burning shell produces more helium, the core increases in mass and temperature. In a red giant of up to 2.25 M☉, the mass of the helium core becomes degenerate prior to helium fusion. Finally, when the temperature increases sufficiently, core helium fusion begins explosively in what is called a helium flash, and the star rapidly shrinks in radius, increases its surface temperature, and moves to the horizontal branch of the HR diagram. For more massive stars, helium core fusion starts before the core becomes degenerate, and the star spends some time in the red clump, slowly burning helium, before the outer convective envelope collapses and the star then moves to the horizontal branch.[88]

After a star has fused the helium of its core, it begins fusing helium along a shell surrounding the hot carbon core. The star then follows an evolutionary path called the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) that parallels the other described red-giant phase, but with a higher luminosity. The more massive AGB stars may undergo a brief period of carbon fusion before the core becomes degenerate. During the AGB phase, stars undergo thermal pulses due to instabilities in the core of the star. In these thermal pulses, the luminosity of the star varies and matter is ejected from the star’s atmosphere, ultimately forming a planetary nebula. As much as 50 to 70% of a star’s mass can be ejected in this mass loss process. Because energy transport in an AGB star is primarily by convection, this ejected material is enriched with the fusion products dredged up from the core. Therefore, the planetary nebula is enriched with elements like carbon and oxygen. Ultimately, the planetary nebula disperses, enriching the general interstellar medium.[89] Therefore, future generations of stars are made of the “star stuff” from past stars.[90]

Massive stars

Main articles: Supergiant star, Hypergiant, and Wolf–Rayet star

During their helium-burning phase, a star of more than 9 solar masses expands to form first a blue supergiant and then a red supergiant. Particularly massive stars (exceeding 40 solar masses, like Alnilam, the central blue supergiant of Orion’s Belt)[91] do not become red supergiants due to high mass loss.[92] These may instead evolve to a Wolf–Rayet star, characterised by spectra dominated by emission lines of elements heavier than hydrogen, which have reached the surface due to strong convection and intense mass loss, or from stripping of the outer layers.[93]

When helium is exhausted at the core of a massive star, the core contracts and the temperature and pressure rises enough to fuse carbon (see Carbon-burning process). This process continues, with the successive stages being fueled by neon (see neon-burning process), oxygen (see oxygen-burning process), and silicon (see silicon-burning process). Near the end of the star’s life, fusion continues along a series of onion-layer shells within a massive star. Each shell fuses a different element, with the outermost shell fusing hydrogen; the next shell fusing helium, and so forth.[94]

The final stage occurs when a massive star begins producing iron. Since iron nuclei are more tightly bound than any heavier nuclei, any fusion beyond iron does not produce a net release of energy.[95]

Some massive stars, particularly luminous blue variables, are very unstable to the extent that they violently shed their mass into space in events known as supernova impostors, becoming significantly brighter in the process. Eta Carinae is known for having undergone a supernova impostor event, the Great Eruption, in the 19th century.

Collapse

As a star’s core shrinks, the intensity of radiation from that surface increases, creating such radiation pressure on the outer shell of gas that it will push those layers away, forming a planetary nebula. If what remains after the outer atmosphere has been shed is less than roughly 1.4 M☉, it shrinks to a relatively tiny object about the size of Earth, known as a white dwarf. White dwarfs lack the mass for further gravitational compression to take place.[96] The electron-degenerate matter inside a white dwarf is no longer a plasma. Eventually, white dwarfs fade into black dwarfs over a very long period of time.[97]

In massive stars, fusion continues until the iron core has grown so large (more than 1.4 M☉) that it can no longer support its own mass. This core will suddenly collapse as its electrons are driven into its protons, forming neutrons, neutrinos, and gamma rays in a burst of electron capture and inverse beta decay. The shockwave formed by this sudden collapse causes the rest of the star to explode in a supernova. Supernovae become so bright that they may briefly outshine the star’s entire home galaxy. When they occur within the Milky Way, supernovae have historically been observed by naked-eye observers as “new stars” where none seemingly existed before.[98]

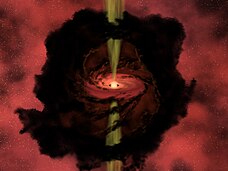

A supernova explosion blows away the star’s outer layers, leaving a remnant such as the Crab Nebula.[98] The core is compressed into a neutron star, which sometimes manifests itself as a pulsar or X-ray burster. In the case of the largest stars, the remnant is a black hole greater than 4 M☉.[99] In a neutron star the matter is in a state known as neutron-degenerate matter, with a more exotic form of degenerate matter, QCD matter, possibly present in the core.[100]

The blown-off outer layers of dying stars include heavy elements, which may be recycled during the formation of new stars. These heavy elements allow the formation of rocky planets. The outflow from supernovae and the stellar wind of large stars play an important part in shaping the interstellar medium.[98]

Binary stars

Binary stars‘ evolution may significantly differ from that of single stars of the same mass. For example, when any star expands to become a red giant, it may overflow its Roche lobe, the surrounding region where material is gravitationally bound to it; if stars in a binary system are close enough, some of that material may overflow to the other star, yielding phenomena including contact binaries, common-envelope binaries, cataclysmic variables, blue stragglers,[101] and type Ia supernovae. Mass transfer leads to cases such as the Algol paradox, where the most-evolved star in a system is the least massive.[102]

The evolution of binary star and higher-order star systems is intensely researched since so many stars have been found to be members of binary systems. Around half of Sun-like stars, and an even higher proportion of more massive stars, form in multiple systems, and this may greatly influence such phenomena as novae and supernovae, the formation of certain types of star, and the enrichment of space with nucleosynthesis products.[103]

The influence of binary star evolution on the formation of evolved massive stars such as luminous blue variables, Wolf–Rayet stars, and the progenitors of certain classes of core collapse supernova is still disputed. Single massive stars may be unable to expel their outer layers fast enough to form the types and numbers of evolved stars that are observed, or to produce progenitors that would explode as the supernovae that are observed. Mass transfer through gravitational stripping in binary systems is seen by some astronomers as the solution to that problem.[104][105][106]

Distribution

Stars are not spread uniformly across the universe but are normally grouped into galaxies along with interstellar gas and dust. A typical large galaxy like the Milky Way contains hundreds of billions of stars. There are more than 2 trillion (1012) galaxies, though most are less than 10% the mass of the Milky Way.[107] Overall, there are likely to be between 1022 and 1024 stars[108][109] (more stars than all the grains of sand on planet Earth).[110][111][112] Most stars are within galaxies, but between 10 and 50% of the starlight in large galaxy clusters may come from stars outside of any galaxy.[113][114][115]

A multi-star system consists of two or more gravitationally bound stars that orbit each other. The simplest and most common multi-star system is a binary star, but systems of three or more stars exist. For reasons of orbital stability, such multi-star systems are often organized into hierarchical sets of binary stars.[116] Larger groups are called star clusters. These range from loose stellar associations with only a few stars to open clusters with dozens to thousands of stars, up to enormous globular clusters with hundreds of thousands of stars. Such systems orbit their host galaxy. The stars in an open or globular cluster all formed from the same giant molecular cloud, so all members normally have similar ages and compositions.[89]

Many stars are observed, and most or all may have originally formed in gravitationally bound, multiple-star systems. This is particularly true for very massive O and B class stars, 80% of which are believed to be part of multiple-star systems. The proportion of single star systems increases with decreasing star mass, so that only 25% of red dwarfs are known to have stellar companions. As 85% of all stars are red dwarfs, more than two thirds of stars in the Milky Way are likely single red dwarfs.[117] In a 2017 study of the Perseus molecular cloud, astronomers found that most of the newly formed stars are in binary systems. In the model that best explained the data, all stars initially formed as binaries, though some binaries later split up and leave single stars behind.[118][119]

The nearest star to the Earth, apart from the Sun, is Proxima Centauri, 4.2465 light-years (40.175 trillion kilometres) away. Travelling at the orbital speed of the Space Shuttle, 8 kilometres per second (29,000 kilometres per hour), it would take about 150,000 years to arrive.[120] This is typical of stellar separations in galactic discs.[121] Stars can be much closer to each other in the centres of galaxies[122] and in globular clusters,[123] or much farther apart in galactic halos.[124]

Due to the relatively vast distances between stars outside the galactic nucleus, collisions between stars are thought to be rare. In denser regions such as the core of globular clusters or the galactic center, collisions can be more common.[125] Such collisions can produce what are known as blue stragglers. These abnormal stars have a higher surface temperature and thus are bluer than stars at the main sequence turnoff in the cluster to which they belong; in standard stellar evolution, blue stragglers would already have evolved off the main sequence and thus would not be seen in the cluster.[126]

Characteristics

Almost everything about a star is determined by its initial mass, including such characteristics as luminosity, size, evolution, lifespan, and its eventual fate.

Age

Main article: Stellar age estimation

Most stars are between 1 billion and 10 billion years old. Some stars may even be close to 13.8 billion years old—the observed age of the universe. The oldest star yet discovered, HD 140283, nicknamed Methuselah star, is an estimated 14.46 ± 0.8 billion years old.[127] (Due to the uncertainty in the value, this age for the star does not conflict with the age of the universe, determined by the Planck satellite as 13.799 ± 0.021).[127][128]

The more massive the star, the shorter its lifespan, primarily because massive stars have greater pressure on their cores, causing them to burn hydrogen more rapidly. The most massive stars last an average of a few million years, while stars of minimum mass (red dwarfs) burn their fuel very slowly and can last tens to hundreds of billions of years.[129][130]

| Initial Mass (M☉) | Main Sequence | Subgiant | First Red Giant | Core He Burning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 9.33 | 2.57 | 0.76 | 0.13 |

| 1.6 | 2.28 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| 2.0 | 1.20 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.28 |

| 5.0 | 0.10 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.02 |

Chemical composition

See also: Metallicity and Molecules in stars

When stars form in the present Milky Way galaxy, they are composed of about 71% hydrogen and 27% helium,[132] as measured by mass, with a small fraction of heavier elements. Typically the portion of heavy elements is measured in terms of the iron content of the stellar atmosphere, as iron is a common element and its absorption lines are relatively easy to measure. The portion of heavier elements may be an indicator of the likelihood that the star has a planetary system.[133]

As of 2005 the star with the lowest iron content ever measured is the dwarf HE1327-2326, with only 1/200,000th the iron content of the Sun.[134] By contrast, the super-metal-rich star μ Leonis has nearly double the abundance of iron as the Sun, while the planet-bearing star 14 Herculis has nearly triple the iron.[135] Chemically peculiar stars show unusual abundances of certain elements in their spectrum; especially chromium and rare earth elements.[136] Stars with cooler outer atmospheres, including the Sun, can form various diatomic and polyatomic molecules.[137]

Diameter

Main articles: List of largest known stars, List of smallest stars, and Solar radius

Due to their great distance from the Earth, all stars except the Sun appear to the unaided eye as shining points in the night sky that twinkle because of the effect of the Earth’s atmosphere. The Sun is close enough to the Earth to appear as a disk instead, and to provide daylight. Other than the Sun, the star with the largest apparent size is R Doradus, with an angular diameter of only 0.057 arcseconds.[138]

The disks of most stars are much too small in angular size to be observed with current ground-based optical telescopes, so interferometer telescopes are required to produce images of these objects. Another technique for measuring the angular size of stars is through occultation. By precisely measuring the drop in brightness of a star as it is occulted by the Moon (or the rise in brightness when it reappears), the star’s angular diameter can be computed.[139]

Stars range in size from neutron stars, which vary anywhere from 20 to 40 km (25 mi) in diameter, to supergiants like Betelgeuse in the Orion constellation, which has a diameter about 640 times that of the Sun[140] with a much lower density.[141]

Kinematics

Main article: Stellar kinematics

The motion of a star relative to the Sun can provide useful information about the origin and age of a star, as well as the structure and evolution of the surrounding galaxy.[143] The components of motion of a star consist of the radial velocity toward or away from the Sun, and the traverse angular movement, which is called its proper motion.[144]

Radial velocity is measured by the doppler shift of the star’s spectral lines and is given in units of km/s. The proper motion of a star, its parallax, is determined by precise astrometric measurements in units of milli-arc seconds (mas) per year. With knowledge of the star’s parallax and its distance, the proper motion velocity can be calculated. Together with the radial velocity, the total velocity can be calculated. Stars with high rates of proper motion are likely to be relatively close to the Sun, making them good candidates for parallax measurements.[145]

When both rates of movement are known, the space velocity of the star relative to the Sun or the galaxy can be computed. Among nearby stars, it has been found that younger population I stars have generally lower velocities than older, population II stars. The latter have elliptical orbits that are inclined to the plane of the galaxy.[146] A comparison of the kinematics of nearby stars has allowed astronomers to trace their origin to common points in giant molecular clouds; such groups with common points of origin are referred to as stellar associations.[147]

Magnetic field

Main article: Stellar magnetic field

The magnetic field of a star is generated within regions of the interior where convective circulation occurs. This movement of conductive plasma functions like a dynamo, wherein the movement of electrical charges induce magnetic fields, as does a mechanical dynamo. Those magnetic fields have a great range that extend throughout and beyond the star. The strength of the magnetic field varies with the mass and composition of the star, and the amount of magnetic surface activity depends upon the star’s rate of rotation. This surface activity produces starspots, which are regions of strong magnetic fields and lower than normal surface temperatures. Coronal loops are arching magnetic field flux lines that rise from a star’s surface into the star’s outer atmosphere, its corona. The coronal loops can be seen due to the plasma they conduct along their length. Stellar flares are bursts of high-energy particles that are emitted due to the same magnetic activity.[148]

Young, rapidly rotating stars tend to have high levels of surface activity because of their magnetic field. The magnetic field can act upon a star’s stellar wind, functioning as a brake to gradually slow the rate of rotation with time. Thus, older stars such as the Sun have a much slower rate of rotation and a lower level of surface activity. The activity levels of slowly rotating stars tend to vary in a cyclical manner and can shut down altogether for periods of time.[149] During the Maunder Minimum, for example, the Sun underwent a 70-year period with almost no sunspot activity.[150]

Mass

Main article: Stellar mass

Stars have masses ranging from less than half the solar mass to over 200 solar masses (see List of most massive stars). One of the most massive stars known is Eta Carinae,[151] which, with 100–150 times as much mass as the Sun, will have a lifespan of only several million years. Studies of the most massive open clusters suggests 150 M☉ as a rough upper limit for stars in the current era of the universe.[152] This represents an empirical value for the theoretical limit on the mass of forming stars due to increasing radiation pressure on the accreting gas cloud. Several stars in the R136 cluster in the Large Magellanic Cloud have been measured with larger masses,[153] but it has been determined that they could have been created through the collision and merger of massive stars in close binary systems, sidestepping the 150 M☉ limit on massive star formation.[154]

The first stars to form after the Big Bang may have been larger, up to 300 M☉,[155] due to the complete absence of elements heavier than lithium in their composition. This generation of supermassive population III stars is likely to have existed in the very early universe (i.e., they are observed to have a high redshift), and may have started the production of chemical elements heavier than hydrogen that are needed for the later formation of planets and life. In June 2015, astronomers reported evidence for Population III stars in the Cosmos Redshift 7 galaxy at z = 6.60.[156][157]

With a mass only 80 times that of Jupiter (MJ), 2MASS J0523-1403 is the smallest known star undergoing nuclear fusion in its core.[158] For stars with metallicity similar to the Sun, the theoretical minimum mass the star can have and still undergo fusion at the core, is estimated to be about 75 MJ.[159][160] When the metallicity is very low, the minimum star size seems to be about 8.3% of the solar mass, or about 87 MJ.[160][161] Smaller bodies called brown dwarfs, occupy a poorly defined grey area between stars and gas giants.[159][160]

The combination of the radius and the mass of a star determines its surface gravity. Giant stars have a much lower surface gravity than do main sequence stars, while the opposite is the case for degenerate, compact stars such as white dwarfs. The surface gravity can influence the appearance of a star’s spectrum, with higher gravity causing a broadening of the absorption lines.[35]

Rotation

Main article: Stellar rotation

The rotation rate of stars can be determined through spectroscopic measurement, or more exactly determined by tracking their starspots. Young stars can have a rotation greater than 100 km/s at the equator. The B-class star Achernar, for example, has an equatorial velocity of about 225 km/s or greater, causing its equator to bulge outward and giving it an equatorial diameter that is more than 50% greater than between the poles. This rate of rotation is just below the critical velocity of 300 km/s at which speed the star would break apart.[162] By contrast, the Sun rotates once every 25–35 days depending on latitude,[163] with an equatorial velocity of 1.93 km/s.[164] A main sequence star’s magnetic field and the stellar wind serve to slow its rotation by a significant amount as it evolves on the main sequence.[165]

Degenerate stars have contracted into a compact mass, resulting in a rapid rate of rotation. However they have relatively low rates of rotation compared to what would be expected by conservation of angular momentum—the tendency of a rotating body to compensate for a contraction in size by increasing its rate of spin. A large portion of the star’s angular momentum is dissipated as a result of mass loss through the stellar wind.[166] In spite of this, the rate of rotation for a pulsar can be very rapid. The pulsar at the heart of the Crab nebula, for example, rotates 30 times per second.[167] The rotation rate of the pulsar will gradually slow due to the emission of radiation.[168]

Temperature

The surface temperature of a main sequence star is determined by the rate of energy production of its core and by its radius, and is often estimated from the star’s color index.[169] The temperature is normally given in terms of an effective temperature, which is the temperature of an idealized black body that radiates its energy at the same luminosity per surface area as the star. The effective temperature is only representative of the surface, as the temperature increases toward the core.[170] The temperature in the core region of a star is several million kelvins.[171]

The stellar temperature will determine the rate of ionization of various elements, resulting in characteristic absorption lines in the spectrum. The surface temperature of a star, along with its visual absolute magnitude and absorption features, is used to classify a star (see classification below).[35]

Massive main sequence stars can have surface temperatures of 50,000 K. Smaller stars such as the Sun have surface temperatures of a few thousand K. Red giants have relatively low surface temperatures of about 3,600 K; but they have a high luminosity due to their large exterior surface area.[172]

Radiation

The energy produced by stars, a product of nuclear fusion, radiates to space as both electromagnetic radiation and particle radiation. The particle radiation emitted by a star is manifested as the stellar wind,[173] which streams from the outer layers as electrically charged protons and alpha and beta particles. A steady stream of almost massless neutrinos emanate directly from the star’s core.[174]

The production of energy at the core is the reason stars shine so brightly: every time two or more atomic nuclei fuse together to form a single atomic nucleus of a new heavier element, gamma ray photons are released from the nuclear fusion product. This energy is converted to other forms of electromagnetic energy of lower frequency, such as visible light, by the time it reaches the star’s outer layers.[175]

The color of a star, as determined by the most intense frequency of the visible light, depends on the temperature of the star’s outer layers, including its photosphere.[176] Besides visible light, stars emit forms of electromagnetic radiation that are invisible to the human eye. In fact, stellar electromagnetic radiation spans the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from the longest wavelengths of radio waves through infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, to the shortest of X-rays, and gamma rays. From the standpoint of total energy emitted by a star, not all components of stellar electromagnetic radiation are significant, but all frequencies provide insight into the star’s physics.[174]

Using the stellar spectrum, astronomers can determine the surface temperature, surface gravity, metallicity and rotational velocity of a star. If the distance of the star is found, such as by measuring the parallax, then the luminosity of the star can be derived. The mass, radius, surface gravity, and rotation period can then be estimated based on stellar models. (Mass can be calculated for stars in binary systems by measuring their orbital velocities and distances. Gravitational microlensing has been used to measure the mass of a single star.[177]) With these parameters, astronomers can estimate the age of the star.[178]

Luminosity

The luminosity of a star is the amount of light and other forms of radiant energy it radiates per unit of time. It has units of power. The luminosity of a star is determined by its radius and surface temperature. Many stars do not radiate uniformly across their entire surface. The rapidly rotating star Vega, for example, has a higher energy flux (power per unit area) at its poles than along its equator.[179]

Patches of the star’s surface with a lower temperature and luminosity than average are known as starspots. Small, dwarf stars such as the Sun generally have essentially featureless disks with only small starspots. Giant stars have much larger, more obvious starspots,[149] and they exhibit strong stellar limb darkening. That is, the brightness decreases towards the edge of the stellar disk.[180] Red dwarf flare stars such as UV Ceti may possess prominent starspot features.[181]

Magnitude

Main articles: Apparent magnitude and Absolute magnitude

The apparent brightness of a star is expressed in terms of its apparent magnitude. It is a function of the star’s luminosity, its distance from Earth, the extinction effect of interstellar dust and gas, and the altering of the star’s light as it passes through Earth’s atmosphere. Intrinsic or absolute magnitude is directly related to a star’s luminosity, and is the apparent magnitude a star would be if the distance between the Earth and the star were 10 parsecs (32.6 light-years).[182]

| Apparent magnitude | Number of stars[183] |

|---|---|

| 0 | 4 |

| 1 | 15 |

| 2 | 48 |

| 3 | 171 |

| 4 | 513 |

| 5 | 1,602 |

| 6 | 4,800 |

| 7 | 14,000 |

Both the apparent and absolute magnitude scales are logarithmic units: one whole number difference in magnitude is equal to a brightness variation of about 2.5 times[184] (the 5th root of 100 or approximately 2.512). This means that a first magnitude star (+1.00) is about 2.5 times brighter than a second magnitude (+2.00) star, and about 100 times brighter than a sixth magnitude star (+6.00). The faintest stars visible to the naked eye under good seeing conditions are about magnitude +6.[185]

On both apparent and absolute magnitude scales, the smaller the magnitude number, the brighter the star; the larger the magnitude number, the fainter the star. The brightest stars, on either scale, have negative magnitude numbers. The variation in brightness (ΔL) between two stars is calculated by subtracting the magnitude number of the brighter star (mb) from the magnitude number of the fainter star (mf), then using the difference as an exponent for the base number 2.512; that is to say:Δm=mf−mb

2.512Δm=ΔL

Relative to both luminosity and distance from Earth, a star’s absolute magnitude (M) and apparent magnitude (m) are not equivalent;[184] for example, the bright star Sirius has an apparent magnitude of −1.44, but it has an absolute magnitude of +1.41.

The Sun has an apparent magnitude of −26.7, but its absolute magnitude is only +4.83. Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky as seen from Earth, is approximately 23 times more luminous than the Sun, while Canopus, the second brightest star in the night sky with an absolute magnitude of −5.53, is approximately 14,000 times more luminous than the Sun. Despite Canopus being vastly more luminous than Sirius, the latter star appears the brighter of the two. This is because Sirius is merely 8.6 light-years from the Earth, while Canopus is much farther away at a distance of 310 light-years.[186]

The most luminous known stars have absolute magnitudes of roughly −12, corresponding to 6 million times the luminosity of the Sun.[187] Theoretically, the least luminous stars are at the lower limit of mass at which stars are capable of supporting nuclear fusion of hydrogen in the core; stars just above this limit have been located in the NGC 6397 cluster. The faintest red dwarfs in the cluster are absolute magnitude 15, while a 17th absolute magnitude white dwarf has been discovered.[188][189]

Classification

Main article: Stellar classification

| Class | Temperature | Sample star |

|---|---|---|

| O | 33,000 K or more | Zeta Ophiuchi |

| B | 10,500–30,000 K | Rigel |

| A | 7,500–10,000 K | Altair |

| F | 6,000–7,200 K | Procyon A |

| G | 5,500–6,000 K | Sun |

| K | 4,000–5,250 K | Epsilon Indi |

| M | 2,600–3,850 K | Proxima Centauri |

The current stellar classification system originated in the early 20th century, when stars were classified from A to Q based on the strength of the hydrogen line.[191] It was thought that the hydrogen line strength was a simple linear function of temperature. Instead, it was more complicated: it strengthened with increasing temperature, peaked near 9000 K, and then declined at greater temperatures. The classifications were since reordered by temperature, on which the modern scheme is based.[192]

Stars are given a single-letter classification according to their spectra, ranging from type O, which are very hot, to M, which are so cool that molecules may form in their atmospheres. The main classifications in order of decreasing surface temperature are: O, B, A, F, G, K, and M. A variety of rare spectral types are given special classifications. The most common of these are types L and T, which classify the coldest low-mass stars and brown dwarfs. Each letter has 10 sub-divisions, numbered from 0 to 9, in order of decreasing temperature. However, this system breaks down at extreme high temperatures as classes O0 and O1 may not exist.[193]

In addition, stars may be classified by the luminosity effects found in their spectral lines, which correspond to their spatial size and is determined by their surface gravity. These range from 0 (hypergiants) through III (giants) to V (main sequence dwarfs); some authors add VII (white dwarfs). Main sequence stars fall along a narrow, diagonal band when graphed according to their absolute magnitude and spectral type.[193] The Sun is a main sequence G2V yellow dwarf of intermediate temperature and ordinary size.[194]

There is additional nomenclature in the form of lower-case letters added to the end of the spectral type to indicate peculiar features of the spectrum. For example, an “e” can indicate the presence of emission lines; “m” represents unusually strong levels of metals, and “var” can mean variations in the spectral type.[193]

White dwarf stars have their own class that begins with the letter D. This is further sub-divided into the classes DA, DB, DC, DO, DZ, and DQ, depending on the types of prominent lines found in the spectrum. This is followed by a numerical value that indicates the temperature.[195]

Variable stars

Main article: Variable star

Variable stars have periodic or random changes in luminosity because of intrinsic or extrinsic properties. Of the intrinsically variable stars, the primary types can be subdivided into three principal groups.

During their stellar evolution, some stars pass through phases where they can become pulsating variables. Pulsating variable stars vary in radius and luminosity over time, expanding and contracting with periods ranging from minutes to years, depending on the size of the star. This category includes Cepheid and Cepheid-like stars, and long-period variables such as Mira.[196]

Eruptive variables are stars that experience sudden increases in luminosity because of flares or mass ejection events.[196] This group includes protostars, Wolf-Rayet stars, and flare stars, as well as giant and supergiant stars.

Cataclysmic or explosive variable stars are those that undergo a dramatic change in their properties. This group includes novae and supernovae. A binary star system that includes a nearby white dwarf can produce certain types of these spectacular stellar explosions, including the nova and a Type 1a supernova.[88] The explosion is created when the white dwarf accretes hydrogen from the companion star, building up mass until the hydrogen undergoes fusion.[197] Some novae are recurrent, having periodic outbursts of moderate amplitude.[196]

Stars can vary in luminosity because of extrinsic factors, such as eclipsing binaries, as well as rotating stars that produce extreme starspots.[196] A notable example of an eclipsing binary is Algol, which regularly varies in magnitude from 2.1 to 3.4 over a period of 2.87 days.[198]

Structure

Main article: Stellar structure

The interior of a stable star is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium: the forces on any small volume almost exactly counterbalance each other. The balanced forces are inward gravitational force and an outward force due to the pressure gradient within the star. The pressure gradient is established by the temperature gradient of the plasma; the outer part of the star is cooler than the core. The temperature at the core of a main sequence or giant star is at least on the order of 107 K. The resulting temperature and pressure at the hydrogen-burning core of a main sequence star are sufficient for nuclear fusion to occur and for sufficient energy to be produced to prevent further collapse of the star.[199][200]

As atomic nuclei are fused in the core, they emit energy in the form of gamma rays. These photons interact with the surrounding plasma, adding to the thermal energy at the core. Stars on the main sequence convert hydrogen into helium, creating a slowly but steadily increasing proportion of helium in the core. Eventually the helium content becomes predominant, and energy production ceases at the core. Instead, for stars of more than 0.4 M☉, fusion occurs in a slowly expanding shell around the degenerate helium core.[201]

In addition to hydrostatic equilibrium, the interior of a stable star will maintain an energy balance of thermal equilibrium. There is a radial temperature gradient throughout the interior that results in a flux of energy flowing toward the exterior. The outgoing flux of energy leaving any layer within the star will exactly match the incoming flux from below.[202]

The radiation zone is the region of the stellar interior where the flux of energy outward is dependent on radiative heat transfer, since convective heat transfer is inefficient in that zone. In this region the plasma will not be perturbed, and any mass motions will die out. Where this is not the case, then the plasma becomes unstable and convection will occur, forming a convection zone. This can occur, for example, in regions where very high energy fluxes occur, such as near the core or in areas with high opacity (making radiatative heat transfer inefficient) as in the outer envelope.[200]

The occurrence of convection in the outer envelope of a main sequence star depends on the star’s mass. Stars with several times the mass of the Sun have a convection zone deep within the interior and a radiative zone in the outer layers. Smaller stars such as the Sun are just the opposite, with the convective zone located in the outer layers.[203] Red dwarf stars with less than 0.4 M☉ are convective throughout, which prevents the accumulation of a helium core.[85] For most stars the convective zones will vary over time as the star ages and the constitution of the interior is modified.[200]

The photosphere is that portion of a star that is visible to an observer. This is the layer at which the plasma of the star becomes transparent to photons of light. From here, the energy generated at the core becomes free to propagate into space. It is within the photosphere that sun spots, regions of lower than average temperature, appear.[204]

Above the level of the photosphere is the stellar atmosphere. In a main sequence star such as the Sun, the lowest level of the atmosphere, just above the photosphere, is the thin chromosphere region, where spicules appear and stellar flares begin. Above this is the transition region, where the temperature rapidly increases within a distance of only 100 km (62 mi). Beyond this is the corona, a volume of super-heated plasma that can extend outward to several million kilometres.[205] The existence of a corona appears to be dependent on a convective zone in the outer layers of the star.[203] Despite its high temperature, the corona emits very little light, due to its low gas density.[206] The corona region of the Sun is normally only visible during a solar eclipse.

From the corona, a stellar wind of plasma particles expands outward from the star, until it interacts with the interstellar medium. For the Sun, the influence of its solar wind extends throughout a bubble-shaped region called the heliosphere.[207]

Nuclear fusion reaction pathways

Main article: Stellar nucleosynthesis

Overview of the proton–proton chain

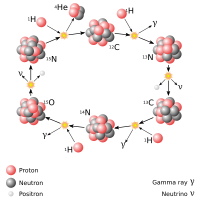

The carbon-nitrogen-oxygen cycle

When nuclei fuse, the mass of the fused product is less than the mass of the original parts. This lost mass is converted to electromagnetic energy, according to the mass–energy equivalence relationship E=mc2

The hydrogen fusion process is temperature-sensitive, so a moderate increase in the core temperature will result in a significant increase in the fusion rate. As a result, the core temperature of main sequence stars only varies from 4 million kelvin for a small M-class star to 40 million kelvin for a massive O-class star.[171]

In the Sun, with a 16-million-kelvin core, hydrogen fuses to form helium in the proton–proton chain reaction:[209]41H → 22H + 2e+ + 2νe(2 x 0.4 MeV)2e+ + 2e− → 2γ (2 x 1.0 MeV)21H + 22H → 23He + 2γ (2 x 5.5 MeV)23He → 4He + 21H (12.9 MeV)

There are a couple other paths, in which 3He and 4He combine to form 7Be, which eventually (with the addition of another proton) yields two 4He, a gain of one.

All these reactions result in the overall reaction:41H → 4He + 2γ + 2νe (26.7 MeV)

where γ is a gamma ray photon, νe is a neutrino, and H and He are isotopes of hydrogen and helium, respectively. The energy released by this reaction is in millions of electron volts. Each individual reaction produces only a tiny amount of energy, but because enormous numbers of these reactions occur constantly, they produce all the energy necessary to sustain the star’s radiation output. In comparison, the combustion of two hydrogen gas molecules with one oxygen gas molecule releases only 5.7 eV.

In more massive stars, helium is produced in a cycle of reactions catalyzed by carbon called the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen cycle.[209]

In evolved stars with cores at 100 million kelvin and masses between 0.5 and 10 M☉, helium can be transformed into carbon in the triple-alpha process that uses the intermediate element beryllium:[209]4He + 4He + 92 keV → 8*Be4He + 8*Be + 67 keV → 12*C12*C → 12C + γ + 7.4 MeV

For an overall reaction of:

34He → 12C + γ + 7.2 MeV

In massive stars, heavier elements can be burned in a contracting core through the neon-burning process and oxygen-burning process. The final stage in the stellar nucleosynthesis process is the silicon-burning process that results in the production of the stable isotope iron-56.[209] Any further fusion would be an endothermic process that consumes energy, and so further energy can only be produced through gravitational collapse.

| Fuel material | Temperature (million kelvins) | Density (kg/cm3) | Burn duration (τ in years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | 37 | 0.0045 | 8.1 million |

| He | 188 | 0.97 | 1.2 million |

| C | 870 | 170 | 976 |

| Ne | 1,570 | 3,100 | 0.6 |

| O | 1,980 | 5,550 | 1.25 |

| S/Si | 3,340 | 33,400 | 0.0315 (~11.5 days) |